A history of violence: trauma-informed approaches towards the foreign women and children of ISIL

An excerpt from my international law thesis: when trauma meets state policy. Intergenerational trauma and security go hand in hand.

“The past is not dead, it is not even past.” - William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun

“You think darkness is your ally, but you merely adopted the dark. I was born in it. Formed by it. I didn’t see the light until I was already a man. And by then, it was nothing to me but blinding. The shadows betray you, because they belong to me.” – Bane, The Dark Knight Rises

Comfortably numb: preface

International law, just like individuals, is shaped by a history of violence. After all, the twentieth-century post-war global order was forged in response to the trauma caused by state-sponsored violence, genocide, and mass population migrations. Born from loss and molded by grief, international law followed the tsunami of trauma left behind after the wreckage of war after war where the daily experiences were littered with distress, death, and decay. Put simply, worldwide societal traumatic experiences turned into the basis of codifying what permissible state behavior is and what it is not.[^1]

The personal was the political, as traumatic experiences informed and thus became embedded into the foundation of international legislative instruments focusing on state responsibility and security. This served as a state-initiated mechanism for societies worldwide to address their history of violence and the trauma caused by it.

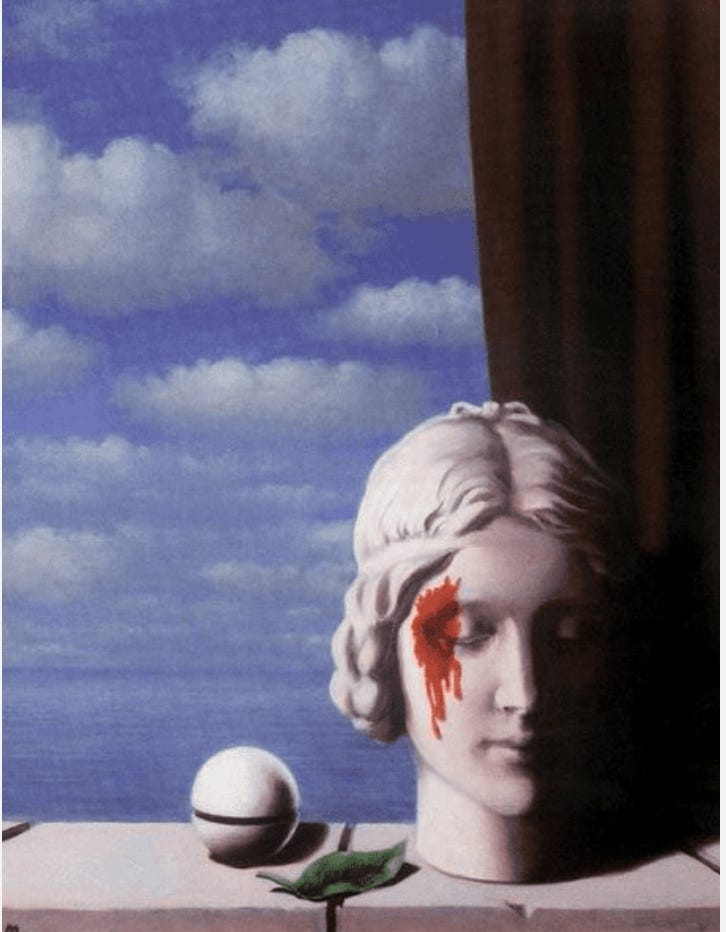

Memory painted by René Magritte, circa 1948.

International law thus promotes progress through pain by shaping state behavior to prevent or mitigate the high cost of human harm while providing a means of coping for affected societies. Yet the idea that progress can be made through pain, as articulated by international law, is limited in scope, as it pertains only to the redemptive narrative of a history of violence on a broad scale. The individual experiences of trauma stemming from events anchored in politics and international security, however, often recede into the historical narrative, becoming akin to distant ship smoke on the horizon.[^2] As such, individual experiences of trauma both legally and politically are not always fully acknowledged or addressed, hindering true progress in addressing and healing from such trauma, despite the proliferation of high-profile trials and tribunals that address the trauma inflicted by authorities on a grand scale.

We have known that trauma from these histories can manifest in various ways, as the examples are as prolific as they are mundane: we intimately know these histories of violence as societies from the macro to the micro, as seen for example in post-war soldiers experiencing erratic behavior due to hearing specific sounds, turning seemingly minor incidents of post-war days into potentially devastating scenarios, or in the recent investigatory explorations of how trauma can literally transform genetics across generations due to epigenetic inheritance of trauma.[^3] Indeed, tsunamis of trauma followed families, communities, and societies struggling in silence to leave the past where it was.[^4]

Subsequently, while traumatic events such as international crimes and atrocities among them have readily informed discussions worldwide in courtrooms, political chambers, and newsrooms, the individual trauma of these events has chiefly remained a personal narrative to grasp, if even acknowledged at all. This can in turn leave individuals and communities struggling to cope with the aftermath of traumatic events in silence, debilitated by trauma and unable to make any narrative of it at all, much less a narrative of progress through pain. At the same time, history begets narrative and narratives beget a historical understanding. We know this from scientific research which has repeatedly shown that narratives, stories, and histories are essential to individuals making sense of their lives.[^5] As such, the failure to recognize, resolve, and provide a means of narrative making for individuals with a history of violence stemming from trauma can leave them without a means of understanding and making sense of their experiences.

So what are these individuals supposed to make sense of or do with a narrative unrecognized or unresolved, which can have detrimental effects on their ability to cope and heal?[^6] Analogously, states create narratives in securitization endeavors, and as such arguably also have a responsibility in creating and shaping narratives for their citizens, since a state’s failure to recognize, resolve, or offer a means of narrative making from trauma on a societal level can impede their ability to understand and make sense of their experiences, as well as those of their citizens, on both institutional and cultural levels. In turn, such a failure hinders the possibility of progress, acknowledgement, and perhaps someday resolution on a societal level.[^7]

If to live is to die, then perhaps purgatory is the twilight state of a life suspended between beginning and end where no narrative exists in between these markers, since trauma occupies that liminal wide space comfortably numbed instead. We intuit this to some extent as a society, since it is now widely known and accepted that individuals living with trauma face numerous barriers, including its impact on physical and mental health, societal taboos, and lack of access to qualified help. For these individuals, suffering does not have clear boundaries, making it difficult to understand and address. This idea of trauma as occupying a liminal space is also increasingly acknowledged in the field of international security as scholars recognize trauma and its application in the field, shifting the landscape of how though trauma is often embedded in international law, politics, and security issues, it is not always fully addressed or understood.

I wanted to preface for readers a foregrounding on trauma precisely because my thesis utilizes a “trauma-informed” care approach (henceforth abbreviated as TIC to encompass the interchangeable terms used in scholarship of ‘trauma-informed care’ or ‘trauma-informed approach/approaches’). Though chapter 3 details further, briefly, TIC is a practice drawing from extensive research in fields such as medicine and psychiatry.[^8] TIC uses an awareness and understanding of trauma psychology and its impacts to then integrate this understanding into practices in a ‘trauma-informed’ way for more effective, humanitarian, and practical results - i.e. TIC has been used to avoid retraumatization and harm in practices and has successfully integrated into practices across fields to improve outcomes.[^9]

Specifically, I examine the issue of the foreign returnee/returning women and children (henceforth referred to as ‘the’ RWAC) of the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL) in regards to how TIC can apply to the political and legal processes surrounding them now.[^10] It is noteworthy how trauma informs the debate between state practices and security expert opinions on the RWAC’s post-caliphate repatriation, as state responses vary and often avoid repatriation, while the consensus of security expert opinions advocate for repatriation and for states to acknowledge trauma in post-repatriation processes.[^11]

Given the complex, controversial, and contentious situation of the RWAC in international security situating them squarely between international law and politics, I kept these parts and pieces about trauma, securitization, and narrative floating around in mind while reflecting on my graduate studies. I found myself returning to the thought about how important narratives are to not just our individual experiences, but their utmost primacy in securitization as well. After all, just like how research has shown that like individuals make narrative meaning of existence, so do terrorist organizations in weaponizing narrative making, as narratives are pertinent in shaping extremist behavior or ideologies influencing individuals towards terrorism or violent behaviors.[^12] Consider how narrative histories of violence are so powerful that even United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 2354 (2017) is specifically about countering terrorist narratives, requiring member states to actively combat them![^13]

Furthermore, to be clear and discussed further in chapter 2 on methodology and research design, it is important to note that this thesis does not aim to advance normative assumptions about trauma. This thesis is not about the securitization of trauma. Rather, I am interested in exploring how trauma may become a securitization issue and to do this, TIC in application to the processes surrounding the RWAC is the chosen way forward.

Reader note: This is not legal advice or anything in the form of advice so don’t @ me with legal tomfoolery. Nonetheless, for comments/consulting inquiries, reach me at ani@anibruna.com. An obligatory message to like and subscribe follows: Like and subscribe for updates. Merci

Footnotes

[^1]: The following examples demonstrate: On Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge, see J. David Kinzie et al., “The Psychiatric Effects of Massive Trauma on Cambodian Children: I. the Children,” Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 25, no. 3 (1986): pp. 370-376, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60259-4. On the Yugoslav wars, see Metin Başoğlu et al., “Psychiatric and Cognitive Effects of War in Former Yugoslavia,” JAMA 294, no. 5 (March 2005): p. 580, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.5.580. On the Iran/Iraq war, see Hassan Shahmiri Barzoki et al., “Studying the Prevalence of PTSD in Veterans, Combatants and Freed Soldiers of Iran-Iraq War: A Systematic and Meta-Analysis Review,” Psychology, Health & Medicine, 2021, pp. 1-7, https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2021.1981408. On the Rwandan genocide, see Déogratias Bagilishya, “Mourning and Recovery from Trauma: In Rwanda, Tears Flow Within,” Transcultural Psychiatry 37, no. 3 (2000): pp. 337-353, https://doi.org/10.1177/136346150003700304.

[^2]: Pink Floyd. “Comfortably Numb”. The Wall, 1979.

[^3]: Natan P. Kellermann, “Transmission of Holocaust Trauma - an Integrative View,” Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes 64, no. 3 (2001): pp. 256-267, https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.64.3.256.18464. See also: Linda O’Neill et al., “Hidden Burdens: A Review of Intergenerational, Historical and Complex Trauma, Implications for Indigenous Families,” Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 11, no. 2 (2016): pp. 173-186, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-016-0117-9.

[^4]: Awais Aftab, “Trauma and the Politics of Diagnosis: Janice Haaken, PhD.” Psychiatric Times, July 13, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/trauma-politics-diagnosis.

[^5]: Robyn Fivush, Jordan A. Booker, and Matthew E. Graci, “Ongoing Narrative Meaning-Making within Events and across the Life Span,” Imagination, Cognition and Personality 37, no. 2 (September 2017): pp. 127-152, https://doi.org/10.1177/0276236617733824.

[^6]: Nina Thorup Dalgaard et al., “The Transmission of Trauma in Refugee Families: Associations between Intra-Family Trauma Communication Style, Children’s Attachment Security and Psychosocial Adjustment,” Attachment & Human Development 18, no. 1 (2015): pp. 69-89, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2015.1113305.

[^7]: A 2014 New Yorker profile on Angela Merkel by George Packer briefly highlights trauma in an anecdote regarding the German government’s political stances towards Russia at the time: “Germans and Russians are bound together by such terrible memories that any suggestion of conflict leads straight to the unthinkable. Michael Naumann put the Ukraine crisis in the context of “this enormous emotional nexus between perpetrator and victim,” one that leaves Germans perpetually in the weaker position. In 1999, Naumann, at that time the culture minister under Schröder, tried to negotiate the return of five million artifacts taken out of East Germany by the Russians after the Second World War. During the negotiations, he and his Russian counterpart, Nikolai Gubenko, shared their stories. Naumann, who was born in 1941, lost his father a year later, at the Battle of Stalingrad. Gubenko was also born in 1941, and his father was also killed in action. Five months later, Gubenko’s mother was hanged by the Germans. “Checkmate,” the Russian told the German. Both men cried. “There was nothing to negotiate,” Naumann recalled. “He said, ‘We will not give anything back, as long as I live.’” George Packer, “The Astonishing Rise of Angela Merkel,” The New Yorker, November 24, 2014, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/12/01/quiet-german.

[^8]: “What Is Trauma Informed Care?,” Trauma Informed Oregon (Regional Research Institute for Human Services, Portland State University, April 15, 2022), https://traumainformedoregon.org/resources/new-to-trauma-informed-care/what-is-trauma-informedcare/.

[^9]: Eve Rittenberg, “Trauma-Informed Care — Reflections of a Primary Care Doctor in the Week of the Kavanaugh Hearing,” New England Journal of Medicine 379, no. 22 (2018): pp. 2094-2095, https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1813497.

[^10]: Readers should note that I refrain from using grammatical articles with the abbreviation RWAC and instead use it as a catch-all term inclusive of the articles when the abbreviation is used due to brevity needs for thesis word count constraints.

[^11]: Elian Peltier and Constant Méheut, “Europe’s Dilemma: Take in ISIS Families, or Leave Them in Syria?,” The New York Times (The New York Times, May 28, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/28/world/europe/isis-women-children-repatriation.html.

[^12]: David Webber and Arie W Kruglanski, “The Social Psychological Makings of a Terrorist,” Current Opinion in Psychology 19 (2018): pp. 131-134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.024. See also Max Taylor and John Horgan, “A Conceptual Framework for Addressing Psychological Process in the Development of the Terrorist,” Terrorism and Political Violence - Volume 18, 2006 - Issue 4 18, no. 4 (2006): pp. 585-601, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09546550600897413.

[^13]: United Nations Security Council Resolution 2354 (2017), https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N17/149/22/PDF/N1714922.pdf?OpenElement