China girl, pt. 3: the economics of exclusion costing us $100 billion a year in American defense when we shut out women

Or: how losing ten MIT graduating classes of female engineers annually cost us $4.5 trillion while China mobilized theirs

Part 3’s subsections:

The STEM pipeline hemorrhage - where we lose women at every transition point

The attrition cost - $2.8-3.9 billion annually in preventable losses

The prime directive needs reworking - how defense contractors fail at parity

The systematic sorting problem - horizontal segregation within engineering disciplines

The economic hit - $100 billion every single year

Let’s get specific about what this culture of exclusion costs us, because I did the math and it’s worse than you think. While China mobilizes 2.85 million women in technical roles who start contributing to military capabilities on day one, America hemorrhages 10,000 to 13,000 female engineers annually. That’s ten MIT graduating classes walking away from engineering every single year.

Part 1 and 2 of this series established the reality that China fields 10 times our drone fleet, closed an 80% AI capability gap in 13 months, and acquires weapons 5 to 6 times faster than us, all while employing 2.85 million women in STEM R&D. Part 2 revealed how we actively repel women through sexualized weapons discourse and hostile culture. Now let’s count what this exclusion actually costs us in cold, hard cash. Spoiler: it’s $100 billion every year.

The STEM pipeline hemorrhage - where we lose women at every transition point

Where and when do we begin to hemorrhage women in defense tech via educational and labor pipelines? I will be doing a fair amount of modeling and estimation for the economics of this post, so it is necessary to also give some context to anchor my choices. Before diving into the numbers, it’s worth establishing why I’m examining the STEM pipeline as it relates to women rather than all defense jobs. Three reasons for this - firstly, STEM roles are the measurable core where we have concrete data on education, employment, and attrition. Secondly, technical positions drive innovation and capability development, they’re the people designing hypersonic missiles, training AI models, and building autonomous weapons systems and the acquisition/achievement of those targets is also something that can be quantified more easily per country. Thirdly and pressingly, China’s Military-Civil Fusion doctrine specifically targets STEM workers as the bridge between commercial and military capabilities. When China reports 2.85 million women in “science and technology” roles, they’re not counting non-STEM staff. They’re counting the engineers and scientists who determine whether you win the arms race. To make an apples-to-apples comparison of strategic capability, we need to compare technical workforces.

These STEM pipeline numbers represent our most measurable strategic loss, but they also dramatically understate China’s full advantage. Remember those 2 million data annotators training China’s AI systems? The majority are women, middle-aged rural mothers processing 20,000 images daily, and they’re not STEM graduates nor engineers. Nonetheless, they’re training the AI models that close capability gaps in 13 months instead of 5-7 years. China mobilizes women across the entire technical spectrum, from PhD physicists designing hypersonic missiles to rural workers labeling training data. For the purposes of analyzing the American defense industry, I’m focusing this cost analysis on STEM roles because that’s where we have comparable data for apples-to-apples comparison. Yet it must be emphasized that every calculation that follows here is also conservative. The real cost of our exclusionary culture extends far beyond credentialed engineers to technicians, manufacturing workers, and every other role where China taps and uses talent we are leaving on the table here in America.

Now, what’s the cost of losing women in the defense industry in the U.S. and what’s the cost of attrition? Here’s how I calculated this step by step via first examining the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) pipeline in the U.S.

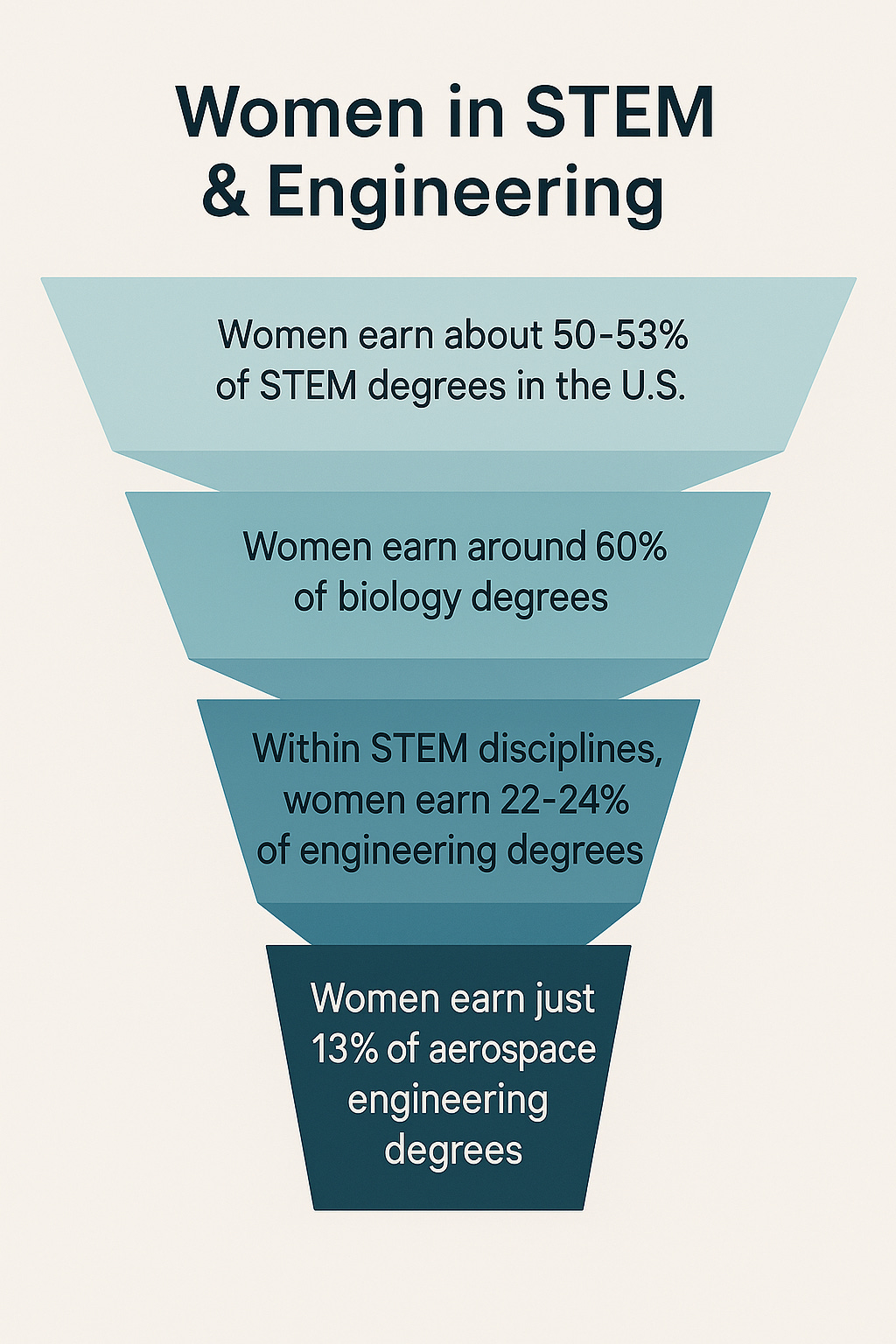

To start, women earn STEM degrees at parity, earning about 50-53% of STEM degrees in the U.S. though upon entering the workforce, women hold around only 34% of STEM jobs. That is already a 16-point drop. Within defense and aerospace, women are just around 20–25% of that workforce which means another 10–14 point drop.

Within STEM disciplines, women earn 22-24% of engineering degrees but make up only 15% of practicing engineers. Mind the gap here, because the graduating cohort of women who get engineering degrees and then leave engineering forever is an astonishing figure.

40% of women who earn engineering degrees leave the engineering field entirely within a few years. They leave not just their job, but they leave the field). Among those who do enter engineering roles, about one in four women leave by their early thirties compared with about one in ten men.

Based on roughly 145,000 engineering bachelor’s degrees awarded annually in the U.S., with women earning about 23% of them, and studies suggesting that nearly 40% of women with engineering degrees either never enter or eventually leave the field, by my estimate, you’re looking at on the order of 10,000–13,000 women per year who earn an engineering degree but don’t stay in engineering long term or leave the field early.

To put this into perspective, that 10,000-13,000 number is roughly about ten to eleven times the annual graduating undergrad class at MIT. More women leave the engineering field in the U.S. every year than ten times the annual graduating undergraduate cohort at MIT.

The attrition gets even more specific when you look at fields. Women earn around 60% of biology degrees but just 13% of aerospace engineering degrees.

Yet aerospace engineering is precisely the discipline most concentrated in defense manufacturing, where approximately 33% of all U.S. aerospace engineers work specifically in aerospace products and parts manufacturing

According to industry reports, aerospace engineering employs only 12-13% women total. In defense manufacturing specifically, the workforce remains overwhelmingly male.

Now, if you treat the roughly 10–13,000 women who leave or never enter engineering each year as a persistent shortfall and translate that into full-time equivalents, what’s the cost of losing these women?

The attrition cost: $2.8-3.9 billion annually in preventable losses

The direct organizational cost of losing 10,000–13,000 women per year from engineering roles relevant to aerospace and defense is on the order of $2.8–$3.9 billion annually.

This is not even including non-engineering roles!

To figure out the economics, I modeled my calculations after two exploratory questions. One, what does an engineer actually cost per year? Two, what does it cost when that engineer quits?

As such, to calculate these costs accurately, we need to understand two separate multipliers that HR professionals use in the form of total compensation and turnover cost.

First, the “total compensation” multiplier is relevant to understand all related costs to an engineer’s pay beyond salary. When Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows median engineer base salary of $106,000, that’s not what they actually cost an employer. Benefits add roughly 42% on top of salary, via health insurance, 401k matching, Social Security and Medicare contributions, paid time off, and other mandatory costs. This means the true cost to employ an engineer is $106,000 × 1.42 = $150,500 per year. This is simply what it costs to have that person working for you annually.

Second, the “turnover cost” multiplier is needed to calculate the cost of when the engineer quits and needs replacing. When that engineer leaves, you don’t just lose their $150,500 annual cost, you also incur massive one-time replacement expenses. According to SHRM’s ANSI-approved framework, highly skilled technical positions cost an additional 100-150% of their annual compensation to replace. That means replacing a highly skilled technical worker costs an additional 1.5 to 2.0 times their annual compensation. The Center for American Progress found that replacing highly skilled workers costs up to 213% of salary, and these replacement costs include anything from the recruiting and hiring (from $20,000-$30,000), training and onboarding (from $15,000-$28,000), security clearance processing for defense roles (from $3,000-$15,000), and 6-12 months of lost productivity while the new hire ramps up.

This is where the math for the attrition costs figure comes in - if we start with $150,500 total compensation per engineer, industry standards say replacement costs run 1.5-2.0 times that amount.

Using a conservative 1.5x multiplier: $150,500 × 1.5 = $225,750 per departure.

For 10,000 women leaving annually, that’s $2.26 billion. For 13,000 departures, it’s $2.93 billion.

Using the upper-bound 2.0x multiplier (which accounts for the specialized nature of particular types of engineering work like aerospace): $150,500 × 2.0 = $301,000 per loss of engineer.

That’s $3.01 billion for 10,000 departures or $3.91 billion for 13,000.

The defensible range is therefore $2.3-3.9 billion annually.

The defensible annual cost therefore ranges from $2.3 billion to $3.9 billion, with the most realistic estimate around $2.6-3.4 billion.

I want to note that this is just engineering attrition alone as defense engineers represent only 18-43% of the defense workforce, meaning women leaving manufacturing, cybersecurity, program management, and other critical defense roles likely represent an equal or greater economic loss.

Even looking at just engineering attrition alone, the most quantifiable part of the talent crisis, we’re losing $2 to $3 billion annually. Yet this still dramatically understates the problem because defense needs far more than just degreed engineers. When you factor in technicians, program managers, analysts, and other critical roles where women are equally underrepresented, the costs multiply. I haven’t calculated those numbers yet, but if someone wants to fund that analysis, my inbox is open

Meanwhile, China doesn’t have this attrition problem. Their female engineers at Alibaba or Tencent don’t leave the field at 2.5 times the rate of men because Military Civil Fusion means they never have to choose between commercial success and national service. They get both. Every female engineer who stays at ByteDance developing algorithms is simultaneously serving defense priorities whether she knows it or not. Zero attrition from the defense pipeline because there is no separate defense pipeline.

Furthermore, there is a leadership paradox in defense, as exceptional female representation at the CEO level masks severe underrepresentation throughout the labor pipeline otherwise.

In recent years, women have held 19% of aerospace and defense CEO positions, which is the highest percentage among major industries and nearly four times the 5% cross-industry average. This historic high emerged during 2018-2019 when four of the top five US defense contractors were led by women with Marillyn Hewson (Lockheed Martin, from 2013 to 2020), Phebe Novakovic (General Dynamics, from 2013 to present), Kathy Warden (Northrop Grumman, 2019 to present), and Leanne Caret (Boeing Defense, from 2016 to 2022).

Yet this CEO success is an anomaly in that it doesn’t tend to cascade downward for other women, as women hold just 25-30% of senior executive roles outside the CEO position and promotion rates reveal systematic barriers. A 2024 McKinsey report found that the situation is actually regressing: for every 100 men promoted to manager in technical roles, only 81 women advance, indicating there is a broken portion of a system that prevents women from building the experience necessary for C-suite positions.

The prime directive needs reworking - how defense contractors fail at parity

At traditional defense contractors, the numbers are stagnant at best overall. Women are 23-29% of the workforce at the big primes with Raytheon at 25%. Boeing’s at 23%. Northrop Grumman at 22% and at the largest defense contractor, Lockheed Martin, women are 23.5% of their workforce as of 2024 (2020 and 2021 at 23.2%, 2022 at 23.3%, 2023 at 23.2%, and 2024 at 23.5%).

That means between them all, it’s the same industry average of roughly 25%, effectively making each defense prime indistinguishable from the pack.

None of the top five U.S. defense contractors have a workforce that’s even a third female.

For Lockheed, this is seven and a half percentage points up from 16% in 1976. That means Lockheed Martin has achieved a rate of change of 0.15 percentage points annually.

At this pace, Lockheed Martin will reach gender parity with the U.S. labor force in the year 2189.

Let me repeat that. 2189.

This crawl confirms we’ll reach parity sometime in the 22nd century. The math checks out: 0.15 times 49 years equals 7.35 percentage points. Starting from 16% women in 1976 gets you to 23.35%, and Lockheed’s at 23.5% today. Right on schedule for that 2189 target.

For the non-traditional defense contractors, reports for gender aren’t available from my research. Meanwhile, remember those 70,000 empty defense positions because we can’t find qualified candidates from Part 1 of this series? If defense contractors matched the general workforce at 47% women, we’d have 275,000 additional workers. That’s almost four times our shortage, but it’s not that we have a talent crisis per se, it’s more so that we have a culture crisis keeping the talented people out.

The systematic sorting problem of horizontal segregation within engineering

Speaking of keeping talented people out, to understand the pipeline issues with women being funneled into defense tech, it’s worth considering how within engineering disciplines, horizontal segregation between engineering specialities reflects segregation patterns that show systematic sorting. As mentioned earlier within the STEM pipeline subsection, consider how biomedical and environmental engineering approach gender parity at nearly 50% women while, mechanical, electrical, aerospace, and computer engineering average only 15% female representation.

How does this happen and why? What may be influencing this trajectory for women and their choice of studies and/or later work within STEM? Some research shows this stems, no pun intended, from perception-based choices. Environmental and biomedical engineering are seen as affording communal goals like helping people and improving health. Technical and aerospace engineering are viewed as working with objects in analytic abstractions. This perception-based sorting has direct defense implications as weapons systems work falls squarely into the object-oriented technical domain that attracts fewer women, but that’s also where fighter jets, bombers, missiles, and combat systems are built.

China doesn’t have this sorting pipeline problem. When your national doctrine treats all technology as potentially military, women working on medical AI at Baidu are as strategically valuable as those designing missile guidance systems at the Chinese defense contractor NORINCO. A communal benefit is built in because serving the nation is helping people. That’s how they maintain 40 to 46% women across their entire technical workforce while we can’t even crack 15% in aerospace.

Further, women selecting environmental or biomedical specialties based on communal goal preferences systematically avoid defense-heavy disciplines. This is paradoxical given the amount of defense work related to biological threats. Case in point: the biodefense startup Valthos is female-founded and just raised $30 million a few weeks before I wrote this.

Software engineering, on the other hand, while also male-dominated, sees higher female representation in certain domains like healthcare tech and educational technology that offer clear communal benefits.

Andreas Baader & Gudrun Ensslin of the Red Army Faction. Photo/article credit - Planet Wissen

Let’s address the elephant in the room. Defense weapons work struggles to sell itself as helping people, which creates a real recruiting problem when women gravitate toward fields with obvious communal benefits, but what the discourse misses is how helping people is the foundational premise of defense - you are defending people!

Defense work already has a powerful ideological draw, it is just framed in all the wrong ways at the moment. The pitch isn’t about helping individuals but about defending a nation full of individuals and their nation’s existential right to survive and thrive. That’s a stronger ideological pull than biomedical engineering’s promise to improve individual health outcomes. Women respond to ideology just as strongly as men do, even if the specific ideologies differ.

History proves this repeatedly. I would invite skeptics who think women are immune to martial ideologies to explain how long-blonde-haired Gudrun Ensslin of Germany’s Red Army Faction differs much from the shadowy veiled women in the Al-Khansaa Brigade who served as the Islamic State’s moral police. Both archetypes were enthusiastic and ardent servants and ideologues for their causes driven by an existential belief.

Our historical mobilization of women during wartime has also drawn upon this as I will detail in the forthcoming part four of this series.

The Al-Khansaa Brigade - photo & article credit: The Guardian

The economic hit: $100 billion every single year

Considering all of the above, the math for the calculations on the economic costs of excluding women are staggering.

If you assume each filled role would generate roughly $200,000 in economic output per year, then 70,000 unfilled defense roles imply about $14 billion in work that simply isn’t happening annually.

The opportunity cost calculation: I’ll explain how I got to these numbers - for back-of-the-envelope purposes, I assume $200,000 in economic output per high-skill worker per year. That’s in line with estimates of U.S. GDP per person employed at around $150,000+ across the whole economy per the World Bank and is actually conservative relative to aerospace and intensive manufacturing, where value added per employee frequently ranges from $185,000 to over $250,000.

Now, if you take an American defense workforce on the order of 1.1 - 1.2 million people, with women currently around 23% and the broader U.S. labor force around 47% female, parity would imply roughly 250,000–300,000 more women in these roles. Using the same $200,000 per worker assumption, that’s on the order of $50–60 billion in additional output per year that we’re not capturing.

Recall how Boston Consulting Group found diverse teams produce 19% more innovation revenue. Apply that to defense R&D at $140 billion annually and from my calculations, homogeneous teams cost us $26 billion in unrealized innovation. That’s the innovation penalty every year. 19% innovation times 140 billion annually means ≈ 26.6 billion lost in unrealized innovation.

Adding onto all of this with the attrition/replacement cost of around 2.6-3.4 billion annually, my estimated model bringing together the loss of work (at 14 billion), the loss of additional output at parity (at 50-60 billion) and the innovation penalty (at 26.6 billion), puts the annual cost of excluding women in American defense at around $100 billion.

If you then apply that gap over half a century, you get something on the order of a few trillion dollars. I’ll walk through how I came to these numbers too.

Consider how according to the National Defense Industrial Association, “‘In 1985, the U.S. had 3 million workers in the defense industry. By 2021, the U.S. had 1.1 million workers in the sector, a reduction of nearly two-thirds.”

In the forty-nine years since 1976 when Lockheed began tracking these numbers, this adds up to something on the order of several trillion dollars in lost value. If you apply that rough $100 billion annual cost over nearly half a century, you end up in the multi-trillion-dollar range, which is on the order of a few to several trillion dollars in lost value. That’s roughly to $4.5-5 trillion, comparable to the annual GDP of a country like Japan, simply because we made defense a hostile place for women. As an illustration of scale, we could have bought the entire GDP of Japan with what we’ve lost by making defense hostile to women.

The U.S. defense industrial base has not just stagnated in the past forty years, it has plummeted by nearly two-thirds from about 3 million workers in 1985 to 1.1 million in 2021. These were the same decades when women began entering STEM in significant numbers.

We lost 66% of defense jobs through consolidation and restructuring, and apparently no one thought to track whether gender played a role in who stayed and who left. The loss of 1.9 million jobs after the Cold War was never analyzed through a gender lens. Meanwhile, China figured out how to use gender equity as a strategic advantage.

Concluding remarks on the economics of exclusion & what’s next for Part 4 of the China girl series:

The economics of exclusion when it comes to shutting women out of the defense industry in America tells a story we don’t want to hear. Every year, America voluntarily burns $100 billion by excluding women from defense technology. Since 1976, that compounds to $4.5 trillion in lost value. Again, that back of the envelope calculation is similar to Japan’s entire economic output. All of it gone, whoosh, up in the air, unrealized, and because we made defense hostile to women.

China gets it, though - they understood that in technology competition, talent is the only currency that matters. While we built elaborate systems to filter women out through clearance delays, financial scrutiny, and cultural hostility, China has elaborate systems and institutional support to pull them in. They turned rural mothers into AI trainers processing 20,000 images daily whilst also ensuring any woman with a STEM degree contributes to national defense capabilities from her first day of work.

The economics are brutal but track with reality. China produces weapons we can’t counter, designed by women we wouldn’t have hired. They deploy AI systems trained by women we would have rejected. They manufacture drone swarms in facilities staffed by women who wouldn’t have survived our clearance process.

We’re not losing because China is smarter. We’re losing because China uses all their smart people while we use half of ours. As I keep advancing throughout this series, China plays Jenga with all the pieces while we voluntarily throw half away. At $100 billion per year, that’s the most expensive mistake in human history.

This is far, far, far away from any galaxy of being a mere “diversity” concern - bringing more women into defense roles (and fixing the culture to retain them) is a national security imperative.

History shows us that the U.S. can do this - from the “Rosie the Riveters” and female codebreakers of WWII to the women who helped put astronauts on the moon - but it requires acknowledging the cost of the status quo to find and enact actionable solutions to it.

The economics of exclusion means we’re eroding America’s capabilities from an angle of contributing to a slower, weaker defense innovation base. Reducing those losses could be akin to adding the GDP of a medium-sized country to our output, but more importantly, frankly, in an era of strategic competition, the U.S. cannot afford to continue writing off half its talent.

The forthcoming Part 4 of this series will examine further structural mechanisms exacerbating the exclusion of women in defense.