Get in loser, we’re going to war: what Mean Girls teaches us about drones

Why Mean Girls is a Pentagon training film about drones, directed energy, and the tactical logic of teenage girls and how defense doctrine can learn from Regina George applied to distributed networks

Is there anyone better at waging war than a teenage girl?

Did your middle school bestie steal your boyfriend of three days named Alex K? (It’s a true story, reader. Last I heard, he is now married to a woman who bears a striking resemblance to his mother and is Hispanic, even though he’s a big Trump supporter/MAGA. Everyone emerged from this battle a winner, methinks.)

If you think violence requires a body count, I have a thesis for you - the iconic 2004 film Mean Girls is the closest thing we have to a US defense doctrine training film on drones and the Pentagon is only now catching up.

We should thank our lucky stars every day it was Carl von Clausewitz and Otto von Bismarck writing military theory, not Carla and Odette. If women had been running war doctrine, they’d have figured this out centuries ago and the rest of us would still be running to catch-up.

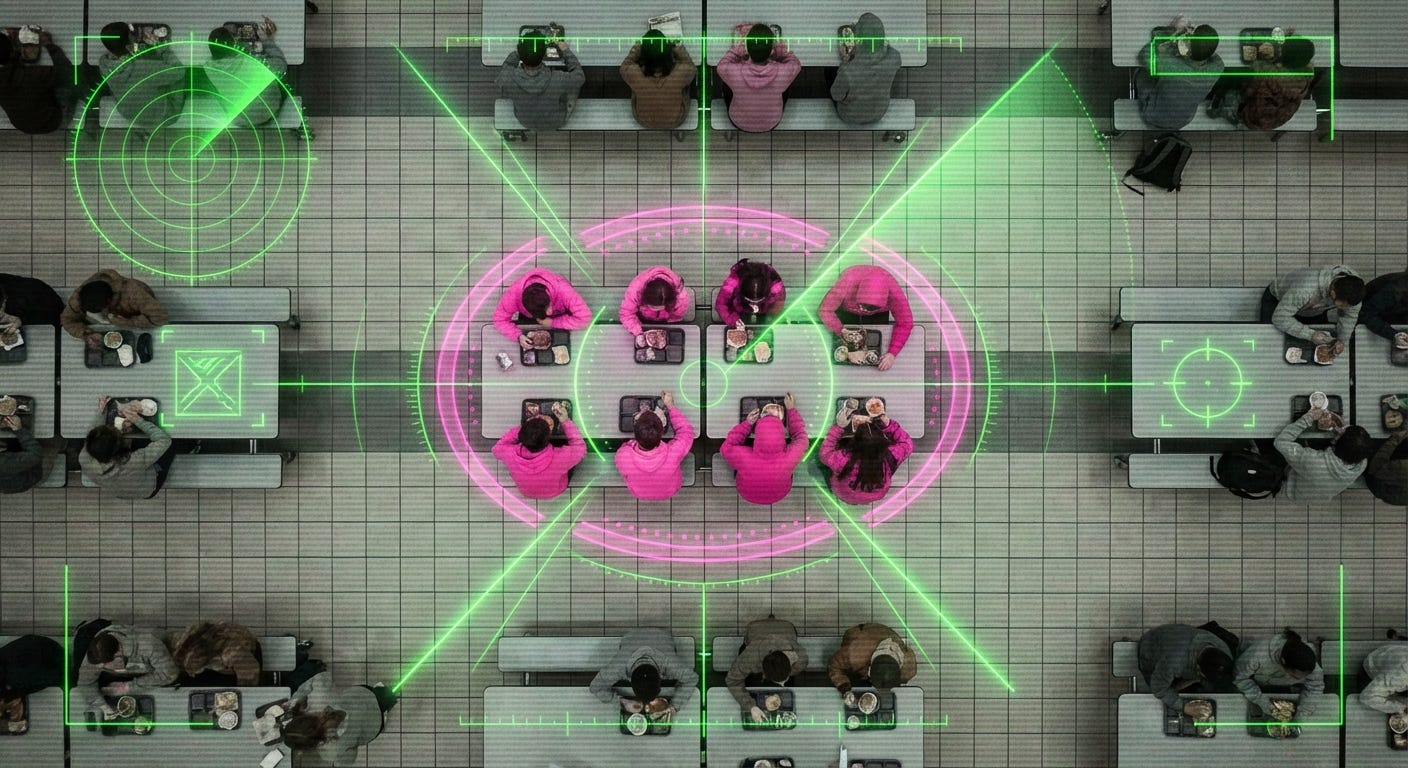

The Pentagon knows this and they just don’t know how to say it out loud - the logic which wins modern wars is the same running American high school cafeterias.

The antagonist of Mean Girls is teenage queen bee Regina George and I’m going to make the case that we are also seeing Regina Drone here given all the parallel structures about drone warfare reflected in the film.

Over the past decade, US defense doctrine has been quietly rewriting itself around concepts like “mosaic warfare,” “distributed lethality,” and “kill webs.” When you strip the jargon away, they’re all describing the same shift in war from big expensive platforms slugging it out in direct confrontation.

We’re instead barreling toward distributed networks of cheap nodes coordinating to overwhelm, deny, and exhaust, just like teenage girls swarm their enemies. It’s not about mortal combat one on one, but power through coordination instead of individual strength and where information is the primary weapon, just like teenage girls disseminate information in their networks.

Nowadays, victory in modern warfare is achieved by making it impossible for your opponent to operate, which is also just like what teenage girls do. If you have never seen teenage girls fighting over a boy, you do not know what hearts of darkness in warfare truly exist. We’re in force multiplier territory, and the force is teenage girls.

Before I point out the parallels between drone warfare and Mean Girls, for those of you who have somehow lived the past twenty one years without encountering this iconic film, a quick run-down of the plot is helpful (it’s not a movie, it’s a film.)

Cady Heron, homeschooled in Africa, arrives at an American high school bright eyed and bushy tailed with zero understanding of its social architecture. She gets recruited by outsiders Janis and Damian to infiltrate the Plastics, the ruling clique of their school composed of three girls led by Regina George. The Plastics maintain power through coordinated social behavior, information warfare (found in their gossipy grimoire known as the Burn Book, a journal full of damaging intel on every girl in school), and rigid access control to their network (”you can’t sit with us”).

Make no mistake about it - the Plastics are a drone swarm and on Wednesdays, they deploy in pink. Individually they are of varying intelligences and capabilities, but collectively they are dominant.

Then there’s Cady herself, who turns out to be a rogue mercenary figure in a cartel. After all, Cady is an outsider with no native understanding of the system, she is recruited by local handlers (Janis and Damian), and then embedded inside the dominant network to learn its tactics from within. She didn’t invent new methods, she absorbs the Plastics’ playbook and turns it against them.

These are of course also the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) used to operate and control drones, and Cady’s experience is just like the first-person view (FPV) drone pipeline in human form, where one goes to where the expertise is, learns from its best practitioners, and then uses those TTPs to deploy against their targets..which is exactly what ends up happening in this tour de force film.

Cady’s infiltration eventually destabilizes the network, hijinks ensue, the whole system collapses, and of course, there is a boy involved between the adversaries. Mean Girls earned Tina Fey multiple screenwriting award nominations, and it should win her a Pentagon consultancy.

Now, if you haven’t been doom-scrolling defense Twitter or violating aerial flight laws for Instagram shots using drones, presuming a reader’s familiarity with the matter, in layman’s terms, I think that your mental health is probably in a better place than most and some quick insights on drones are worthwhile.

Drones are cheaper than Botox injections nowadays and by that I mean they’re cheap-cheap. You can get one for around $500. They are hella handy as one would say in the Bay area where I’m writing this from, and drones are ready to hand because they are present to hand cameras, bombs, Amazon deliveries, or perhaps even all three at once nowadays (someone send this to Palmer Luckey to verify please and do not mistake this for Heidegger’s meanings).

Drones can fly in coordinated groups called swarms where they share information and attack from multiple directions at once. In Ukraine, they’re responsible for the majority of battlefield casualties. The old way of war was building a $120 million fighter jet and hoping it survives. The new way is sending 100 drones that cost less than a used Honda Civic and not caring if you lose half of them. That’s so fetch, as one of the Plastics would say. It democratizes warfare in a way that also breaks everything the Pentagon was built to do with heroic single combat. Gone are the days of Maverick in Top Gun (some would say that’s a film too) with one pilot, one jet, one kill. What government actors are facing now is death by a thousand paper cuts from enemies who learned their tactics on YouTube and bought their hardware online.

Sound familiar? It should.

1. Fear and loathing in the cafeteria

Do you know what happens if you cross the drone swarm leader? You will be met by an assault from all corners clothed in various shades of pink as they swoop in on you.

What makes the Plastics terrifying is not Regina herself, who is just the node with the highest status, but rather the fact that they operate as a coordinated system with simple rules - you sit here, wear this, hate her, don’t eat carbs on Tuesdays. When we hear the rule that “On Wednesdays we wear pink”, we’re hearing about the drone coordination protocol, a low-bandwidth, high-clarity signal that shows being synced with the swarm. Violate it and the error handling is immediate - social ostracization as “You can’t sit with us.”

This is exactly how engineers model drone swarms. Like the Plastics, you don’t need each drone to be smart. You just need them all following simple rules and responding to the same signals. There’s power in numbers, so maintain X distance from the nearest friendly, prioritize target class Y, and if jammed, switch to fallback behavior Z. The hive mind intelligence of the drone swarm is distributed in the network, it isn’t beholden to any single node, which is an assignment China most certainly understood.

Their Jiu Tian drone mothership is a 16-ton high-altitude aircraft that can deploy up to 100 smaller attack drones from 50,000 feet. Imagine Regina George with a 25-meter wingspan, where the central coordination node gives the swarm its power and its direction, and all else follows the leader. The actual violence emanates from Regina Drone across all those little loitering munitions fanning out beneath her. Kind of awing, really, in a morbid way.

The thing about Regina, though, is that her power looks invincible until you realize she’s a single point of failure, and Jiu Tian has the same problem. Put that over the Taiwan Strait and you run into the dilemma where Regina Drone is huge, non-stealthy, and flying predictable paths at predictable altitudes. Huge targets get shot down, like how in the film Regina meets a bus…but what about all the small drones she’s already deployed? What happens to the other Plastics once Regina is out of commission?

2. Regina Drone’s high-G hair flip

Imagine your middle school bestie who stole your boyfriend of 72 hours regenerating over and over again no matter how many times you tell people to write nasty things in her yearbook.

Chinese researchers have developed something not too dissimilar with what’s called “terminal evasion,” bolting tiny side-mounted rocket boosters onto drones so they can pull 16G lateral maneuvers in the final second before a missile hits, and in simulations survival rates jump from around 10% to 87%. When a missile is incoming, in the final second before impact the boosters fire and the drone jerks sideways with 16G of force, all that force and violence and fast, fast, fast maneuvering due to the supports means the missile sails right past. Regina Drone lives to see another day. 16G would kill a human, as to put it clinically, your organs would crush, but drones don’t have organs.

Consider what this means from a defense perspective. You launch an interceptor (a missile designed to catch and kill other flying things) that costs $1-3 million, it locks onto a drone that cost maybe $10,000, the interceptor is screaming toward its target, and then at the last possible moment the drone does the tactical equivalent of “Oh my god, I love your bracelet” and sidesteps out of the kill zone, hurtling all your efforts with this expensive missile towards hitting nothing at all. Meanwhile, the cheap drone just keeps living, as American actor Matthew McConaughey is so fond of saying and naming his charity foundation after.

From a cost and effort standpoint, this is devastating for traditional air defense. Your probability of a kill, much less a clean strike becomes moot, your $3 million interceptor is now trading against a $10,000 drone that might just move, and your entire system assumes the target would cooperate by flying in a straight line. You thought you were in a duel, the drone knows it’s in a network, and a triangle requires a metaphor I am too tired to write about right now to be honest.

So if you can’t shoot them down one by one, what’s left?

3. “You can’t sit with us” - access denial as electronic warfare

One of the Plastics’ main tools is access control - you can’t sit with us, you can’t wear a ponytail more than once a week, you can’t wear sweatpants on Monday. Reframe what would be considered bullying somewhere as protocol elsewhere, and this access control is the same thing as jamming in electronic warfare.

Drone jamming is when your drone thinks it has a warm welcome in the radio frequency spectrum, a nice stable link to its controller, and then suddenly the signal gets mean-girled off the network. The connection has been cut, denied, sayonara, goodbye, and your drone doesn’t know what to think anymore. Alone and confused, your jammed drone is either falling out of the sky or flying in circles until its battery dies.

Trading $3 million missiles for cheap drones takes up way too much money, so the Pentagon has shifted towards a new strategy where instead of shooting them down one by one, they’re frying whole swarms at once with directed energy weapons.

In September 2025, a system called Epirus Leonidas, which could be charitably described as high-power microwave, basically a truck-mounted brain fryer, neutralized 61 of 61 drones in a live-fire demo, including 49 in a single pulse. With the push of one button, 49 drones dropped out of the airspace, like Lucy in the sky with cooked electronics. In April 2025, the UK tested something called RapidDestroyer in Wales, which is a place where no one really knows it, by the way, and this RF directed-energy weapon took out more than 100 drones across multiple swarms at a cost per kill of roughly 13 cents.

These systems are peak jamming because they exist to fry a drone’s capabilities instead of not trying to hit it. Jamming doesn’t care about terminal evasion maneuvers and it doesn’t need to, because once systems are down, it’s game over. In colloquial words, once your drone is jammed, you’re cooked. If Mean Girls had an electronic warfare scene, it would be when the beleaguered and exasperated math teacher Ms. Norbury also colloquially cooks (not literally) by photocopying the Burn Book and tossing it into the hallway to reveal its secrets to all students.

Ms. Norbury is doing the jamming here because it’s instant network collapse for the Plastics as everyone’s secrets are out there everywhere, and their all powerful system has collapsed in on itself choking on its own information. So defense has an answer through jamming and directed energy, but does this actually work long-term, does ‘don’t shoot but fry’ scale?

4. The limit does not exist (not even between civilian and military)

One of Cady’s big moments in the film involves solving a high school math question, and her response is in the line “The limit does not exist.” She’s talking about a mathematical function that approaches infinity, and she’s also accidentally describing drone economics. There is no limit left to who uses drones for what, when, where, and how.

Cady starts off as a civilian and by the end of the film becomes a militant figure like Regina. That’s modern drone warfare now where the limit does not exist anymore between military and civilian.

The same DJI quadcopter nephew got for Christmas is being strapped with grenades in Ukraine. The same tech that does vineyard mapping and Amazon deliveries is doing reconnaissance for artillery strikes. The same FPV racing drone a teenager flies for YouTube content is the same one cartels like Jalisco Nueva Generación are using to drop explosives on Mexican police.

There’s no “military drone” and “civilian drone.” There’s just drones, and anyone with $500 and a YouTube tutorial can enter the chat. When the limit does not exist, neither does a barrier to entry.

5. So you agree? You think swarm warfare is really pretty?

Mean Girls is a film about networked power, who has it, how it spreads, and what happens when the underlying rules change. Drone warfare is the same thing, just without pink cardigans and insults about your weight replaced by shrapnel.

China’s mothership drone Jiu Tian is Regina with a 25-meter wingspan, the directed energy jammers Leonidas and RapidDestroyer are Ms. Norbury with a stack of photocopies and absolutely zero patience, and Cady is like a rogue cartel figure infiltrating the kingdom ruled by the Plastics to usurp them using the same technologies, tactics, and procedures.

The logic of teenage girls at warfare in high school as drone warfare scales.

You go from football turf to cartel turf to a South China Sea turf standoff, all of this made possible by cheap nodes, fast information, and the social physics of the machinery coming together.

Holy fuck. This was very good. Gonzo, inventive, and made me laugh while learning stuff. Bravo Ani!