Love in the time of long vol: how the Black-Scholes is actually about desire & attraction

On pricing what you don't know, and deciding whether the uncertainty is worth staying in. Though sometimes you can just go to Canada for a bit if you're long vega.

The global economy runs on derivatives, which are just contracts that price uncertainty, and our private lives run on desire, which does the same thing, but no Greek letter captures the volatility associated with the man who kissed me in the most unexpected way in the most unexpected place that contradicts everything.

So dizzying is the uncertainty of whether I’ll hear from him or not, the uncertainty of the countless other fires in my life, the uncertainty of what happens when I leave the country in a week and what that bears for my goals for my career, much less if I’d be on this person’s mind (and vice versa), that instead of figuring out what any of it means, I’m writing an essay about the Black-Scholes formula that prices uncertainty because I don’t know what to do with uncertainty in my life. What I am certain of, however, is my thesis that attraction is volatility.

Since volatility is the star of the Black-Scholes model as the variable everything else orbits (because the more volatile something is, the more valuable the option on it becomes), that means that the cost of not knowing what happens next is also the engine of desire.

That’s why this options pricing model that sounds like a nefarious law firm is actually a way we can understand something about attraction and maybe ourselves.

1. Kiss off: how options pricing is actually derived from the desire

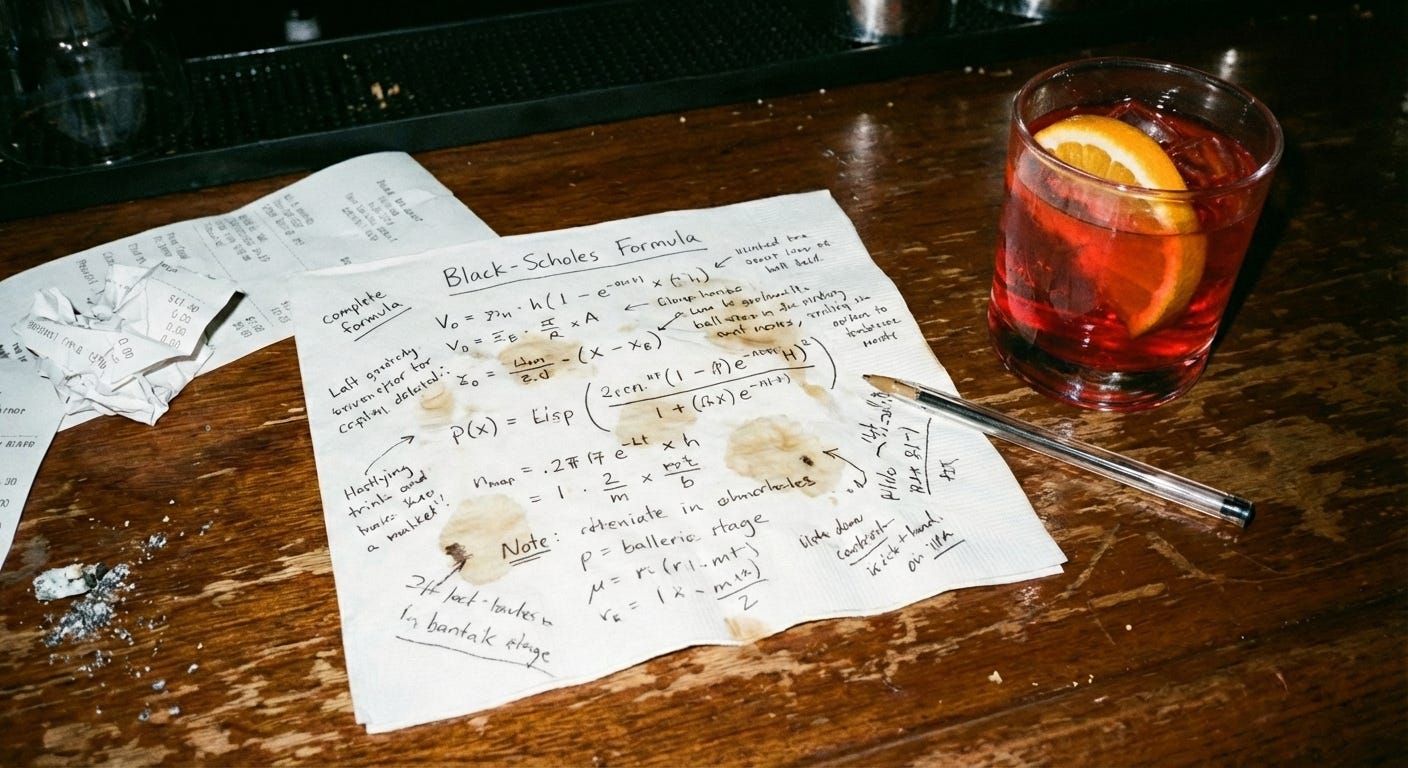

In 1973, the economists Fischer Black and Myron Scholes solved a problem that had haunted finance for decades: how do you price uncertainty? Specifically, how much should it cost to buy the right, but not the obligation, to do something later, once you have more information? The formula changed finance forever. Similarly, when you meet someone whose future moves you cannot predict, your nervous system prices that uncertainty to make it feel like excitement, anticipation, or even need (in lieu of trauma bonding, attachment styles, and whatever else is in the zeitgeist of self-evolving nowadays). Every single person that you have ever wanted to take to bed has been your body running Black-Scholes this whole time.

For those blissfully unaware of the Black-Scholes before reading this post, a brief explanation here is helpful. Black-Scholes prices financial instruments known as options. A call option gives you the right to buy something at a set price by a set date. A put option gives you the right to sell. You pay a small fee upfront, called a premium, for this right. If you’re wrong, you lose the premium. If you’re right, you can make multiples of what you paid. Capped downside, uncapped upside means the asymmetry is the appeal. Do you know what else is also asymmetrical? The fact that I had to learn about Black-Scholes during a set of 6 week lectures spanning 4.5 hours every Saturday and Sunday during the prime exact weeks where there is actually consistent sun in the Netherlands.

When it comes to options, think of it like buying someone a drink and where that can go. Sixteen dollars for a campari is the premium. You’re purchasing the right, not the obligation, to a conversation. If something happens, you exercise into a phone number, a walk, maybe a night you’ll think about for months. If nothing happens, you’re out sixteen dollars, maybe some dignity, and definitely lost time. That is the price of keeping your options open, literally.

Black and Scholes figured out you can calculate what that premium should be if you know five things: where the stock is now, the price you’re betting it crosses, how much time you have, the opportunity cost of your capital, and how much the stock tends to move around. That last variable is called volatility. It’s measured by standard deviation, which is the number that captures how far things tend to swing from their average. I know some of you forgot what it means because you repressed your statistics course memory and TikTok has rotted your brain, so it’s fine, I get it.

Consider how a stock that goes up 1% then down 1% then up 1% has low standard deviation. It’s calm and predictable, whereas a stock that goes up 8% then down 12% then up 15% has high standard deviation as it is chaotic and volatile. The individual experience of holding these two stocks is completely different even if their average return is identical.

Now imagine two people’s moods on a scale of 1 to 10 over five days. To make this example stick, imagine they are people you have had entanglements with.

Person A goes: 6, 7, 6, 7, 6. They text you good morning. They text you goodnight. You go to dinner on Thursday. It’s nice. You go to dinner next Thursday. It’s nice again. You know exactly what you’re getting and you’re getting it. The experience with them resembles a fad about a set of numbers children are constantly calling out instead of embracing the classic of how seven ate nine.

Person B goes: 2, 9, 3, 10, -5, then 11, because this man is the spinal tap. You have an innocuous talk with them that initially feels like you’re pulling their teeth, you say something autistic about how just let me know what time to wrap this up, and then he’s kissing you at a transit point, and also is the same person who won’t look at you as you leave because they are enraptured with their phone. I’m not sure what to make of those signals.

When you calculate the numbers out, they can have the same average but it feels like a completely different experience depending on who it is. Person A is calm while the experience of being around Person B is not always that. Person B has high standard deviation. Person B is volatile. Person A has low to no standard deviation. Person A is low volatility. Person A has inspired someone’s writing somewhere to justify their life, much like Person B has inspired my writing to justify it in my mind.

Volatility in markets is how much a stock moves. Volatility in attraction is how much someone moves you. It all maps out when you consider the five Black-Scholes inputs of current stock price, strike price, time to expiration, interest rate, and volatility - and how they connect to attraction.

2. Add it up: how the Black-Scholes variables connect to attraction

So how exactly does each variable of Black-Scholes map onto attraction?

S, the current stock price, is where you are with them right now. “We matched but haven’t met” is a different starting point for value than “your husband is a good kisser.” Everything else is calculated from here.

K, the strike price, is the threshold you’re betting they’ll cross. It’s the line in the sand like “I’m betting they’ll want something serious by month three”, “I’m betting they will introduce me to their company holiday party this year”, or “I’m betting that the person drowning in a room full of people who all want something from them stops choosing the chemical that makes you feel like love is everywhere and nothing hurts because that’s how people end up accidentally dying, and I don’t know what happens when someone realizes the thing they thought was nourishing them is the thing destroying them visibly.”

Something like that. All thresholds, all bets, all lines in the sand. The further that strike is from your current reality, the cheaper the fantasy and the less likely it pays off. That part I also find dizzying, personally.

T, time to expiration, is the deadline. “They’re moving in six months.” “If they don’t text by Saturday I’m done.” Every option has an expiration date. After that, it’s worthless. The less time you have, the more every interaction matters. This is why I think, for example, vacation flings hit so hard. You’re at expiration, and everything is maximally charged. The scarcity is inherent to the entire pricing mechanism. It’s also how some of my friends have ended up married to foreigners, which has another set of results entirely.

r, the interest rate, is opportunity cost. Every hour spent refreshing their Instagram is an hour not spent on your work, your friends, someone who might actually show up for you, or with a therapist who is a professional trained to understand and treat this neuroticism. We treat attention like it’s free, but it’s your most expensive asset. The carrying cost of obsession is everything else you could be doing with your life, like reading much of my other writing.

σ, volatility, is attraction itself. How much they keep you guessing, how much uncertainty they generate in your nervous system.

Black-Scholes highlights to us how options become more valuable as volatility increases. The model says uncertainty is worth paying for. But now that we’ve established volatility drives attraction, here’s the catch - there’s volatility you expect and the volatility you actually get.

3. Blister in the sun: implied volatility vs realized volatility & why you are deeply unhappy in your relationship’s reality

Four of the five inputs are observable as you can look up the stock price, the strike, the time, the rate. But you don’t actually know future volatility since it hasn’t happened yet. The entire Black-Scholes model depends on a number you have to guess, which is why traders work with two numbers via implied volatility and realized volatility.

Implied volatility is what the market expects as extracted from what people are willing to pay right now. Realized volatility is what actually happens. If everyone in your neighborhood suddenly starts paying triple for home insurance, you can infer they’re expecting a disaster. Nobody had to tell you. The prices revealed the belief. But the disaster might never come. The gap between what people expected and what actually happened is the gap between implied and realized.

Implied volatility in attraction is fantasy. It’s the dating profile, the first date, their reputation, whatever projection you have built from limited data about the person scrambling your brain due to pesky hormones or unresolved past life contracts or some death drive. Realized volatility is who they actually are, masks off, what happens when you spend real time together in the reality that emerges after the projections burn off.

The gap between implied volatility and realized volatility is where most romantic suffering lives.

You thought they were going to be exciting with some mystery, edge, intensity, maybe they’re kinky. The implied vol is high, but they turned out to be boring, predictable, and a proud Swiftie or something. Realized vol is low. You overpaid for the option. Classic disappointment, sorry, you’re sleeping with someone mid. Or the reverse: you thought they’d be safe and predictable. Their implied vol is low, but they turned out to be chaos with a sheer force of depth, damage, and disaster that was hidden. Your realized vol is high as you were unprepared for what you bought. It’s not that they are kinky, it’s that they are sheer chaos.

What I think is that the real best trade, the arbitrage, is finding someone where implied vol is mispriced. They look boring on paper but they’re fascinating in person. They look chaotic on the surface but the underlying asset is actually stable. Reading the fundamentals under the price action, that’s the trade of a lifetime if you’re a romantic. Or Midwestern, I guess.

4. Good feeling: how delta, theta, gamma, and vega describe the emotional exposure, time decay, instability, and uncertainty of attraction

Options traders use something called “the Greeks” to describe how their positions behave - these are known as delta, theta, gamma, and vega. If Black-Scholes tells you what an option is worth right now, the Greeks tell you how that value changes when conditions shift. They’re the dashboard. They tell a trader how exposed they are if the stock moves, how much value they’re losing every day they hold the position, how unstable things get near a deadline, and how sensitive the whole thing is to uncertainty itself. Each one measures sensitivity to a different variable and I think they measure onto relationship dynamics with eerie precision.

Delta is emotional exposure, or how much your mood moves when they move. Delta runs from 0 to 1 for calls (negative for puts, but the idea is the same). At 0, you feel nothing. At 0.1, you’re mildly interested. They’re cute, whatever. At 0.5, your day bends around their behavior. Good text, good day. No text, you’re checking your phone in the bathroom at dinner. At 0.9, your emotional state is tracking theirs in near-perfect lockstep. At 1.0, you are them. Your mood is their mood. This is codependency wearing a trench coat. Think of someone you matched with on an app and never met. Low delta. Think of someone you’ve been sleeping with for four months who won’t call you their girlfriend. The delta is 0.9 and you both know it. Also girl, dump him.

Theta is time decay. Options bleed value every day since like a situationship, the clock eats your investment. Every day you don’t know where you stand, you’re paying theta. Every week of “let’s just see where things go” turns into a month as time marches on. What is mildly annoying at month two is excruciating at month eight because theta accelerates. You feel this in any relationship once the resentment begins. You know exactly what month it stopped being fun and became a burden. You also know that theta benefits sellers. The person with less investment is collecting the premium of your attention without paying any carrying cost. You’re buying, they’re selling, the short side always has the better deal.

Gamma is instability near the moment of truth. The closer you get to a decision point, the more unstable everything becomes. Small signals can produce wildly different interpretations. “They said ‘I had a great time’ with a period instead of an exclamation point.” Crisis. “They took two hours to respond. Usually it’s forty-five minutes.” Catastrophe. This is why people spiral before The Talk. Every text is either confirmation or annihilation. There is no neutral input. This is also why I don’t text as much as possible or keep things short/curt/neutral. Texting is a weapon of mass destruction. I am a woman in my thirties, I do not need to belabor a point by sending paragraphs and blowing up a phone. Seriously, people, it isn’t worth it. Miscommunication abounds, dopamine spikes, disaster much?

Vega is your relationship to uncertainty itself (not the person), to the not-knowing as an abstraction. Some people are long vega: they’re aroused by not knowing. They lose interest the moment someone becomes available because the chase was the point and resolution kills it. Some people are short vega as they need clarity to function and ambiguity causes them pain. Uncertainty isn’t exciting to some people while others need it to breathe. Most relationship failures are vega mismatches. One person’s “we’re just vibing” is the other person’s nuclear event. Neither is wrong, but they’re just positioned differently relative to volatility. They have opposite vega. If you’re wondering which position I hold here, my vega is that I’m going to a cabin in Canada for a month and I’m pretty sure that as much as someone wants to say out of sight, out of mind, I’m just not a person you forget, but maybe I forget.

5. Gone daddy gone: the problem with assumptions about volatility

The Black-Scholes model and its assumptions have problems, like the ones that blew up Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) in 1998, the global economy in 2008, or that YouTube options guru’s entire Discord on Christmas 2025.

Black-Scholes assumes volatility is constant, but people change. Your model of them at month one is already wrong by month four. Your ex who bored you might be fascinating to someone else who decides to marry him and doesn’t know he randomly emailed you right before their wedding. The person who consumed your every thought for years might one day bore you. The model doesn’t account for people becoming different people. The model doesn’t account for people encountering different people. Worse still, the model doesn’t account for when people become different people as a result of who they encounter.

The model also assumes your bets are uncorrelated. That your career, your friendships, your hobbies, your sense of self are all independent of one relationship. How many people do you know where this is actually the case? For example, the SNL skit Man Park always brings to mind how to consider the social lives of men and their dependence relative to a female partner’s network. What happens to that social fabric when the relationship ends? On paper, it becomes the end of all endings, but the reality of that is assuming the same network is one that stands to withstand any extreme event to begin with. You can't stress-test the status quo enslaving you without first allowing for new mental models, and most people aren't ready for that. What I find more overwhelming is denying that, because assuming that dominoes always fall in line is a dangerous assumption when it comes to romance and in reality. For example, LTCM assumed their diversified bets wouldn’t correlate. In the Russian debt crisis of 1998, correlations spiked to 1, then everything crashed at once.

Reality for LTCM disagreed just like it does in relationships. Romance does that, too depending on how entwined things are, as your friends, career, hobbies aren’t separate bets. They’re linked, which means one crisis and your emotional portfolio collapses. It becomes havoc and engulfment where the considerable degradation of emotional experience reflects in the worst possible way that a “diversified” emotional portfolio was one big bet the whole time, and one skewed not at all to your advantage. It’s exhausting and the opposite of life-affirming, if not one of the biggest signals of something that is not working in reality.

Reality can also be something like meeting someone you’re attracted to while believing you’re madly in love with someone else already, and the model assumes you can exit cleanly which is no small feat. In markets, you click “sell” and it’s done. Feelings can outpace readiness or circumstances can cause complications, but you can’t click sell on a relationship. Exits can be messy and sometimes they’re also engineered to seem impossible because of their structure to prevent it to begin with, which lends new meaning to the phrase no exit. Sometimes the same person is both the market maker and the compliance department, so they set the prices, surveil the trades, and call it risk management. Their leverage is emotional, baked into counterparty positions, and allows them to exploit that asymmetry to make a trade where someone becomes a captive position without realizing they were ever being priced. It’s kind of a genius move if you think about it, because it means someone becomes a call option held at a strike price that never needs to be exercised as long as the primary position doesn’t blow up. The option never realizes it’s the product, not the trader.

All the convexity flows one direction, and it is to the benefit of one person who exploits this asymmetry. Some structures exist not to make people happy but to keep them available, which is part of the asymmetric upside they don’t profit from because it is being extracted from them. They pay a premium in being the out-of-money call option.

Sometimes this goes on for years, decades, or a lifetime. Sometimes this involves kids, sometimes it does not. Sometimes some people remain married to someone until their last child is 18 and has left the home. All sorts of volatilities are occurring behind closed doors you’ll never peek behind.

Sometimes you realize that there is no clarity to this reality, at least for now, because sometimes people run multiple positions that contradict each other in their own form of doing risk management. Sometimes you encounter a person so acutely in pain that the public performance takes precedent over their actual well-being. Many such Instagram cases.

Sometimes an entire life can be built on the idea that volatility can be modeled, measured, traded, but some people themselves exceed the instrument and its capabilities.

6. Violent femmes: when the model breaks but it’s liberating since volatility is not risk, but possibility, and that’s beautiful, really

Spectacular blow ups in finance occur when people forget they are merely using a model, just like we do when we’re attracted to a person and built a model of who they are, all of this rallying fueled by desire. When reality diverges, we don’t always update the model, but instead deny what’s in front of us.

Black-Scholes tells me that the spark I feel is not chemistry, but not even a spark to begin with - it’s just the spark of uncertainty. It’s not knowing where I stand since the uncertainty generates perceived value for some, and volatility inflates that premium I keep paying because the option feels expensive, which my brain interprets as worth something.

But volatility is not value, much like excitement is not compatibility. An option on a volatile stock isn’t inherently better than an option on a stable stock. It’s just priced differently, and the excitement of the volatile option doesn’t mean it’ll pay off. It might expire worthless. So thanks for nothing, because the model is useful but the model is not real. Yet there’s a part that the model gets wrong that I think I might be getting right - volatility is not about risk at all, but about possibility.

The model assumes volatility is risk. Something to hedge against, neutralize, minimize.

When I say what if volatility is not risk but possibility, I mean that the beauty inherent to volatility is to be celebrated for its expansiveness rather than reduced to what it represents. We expand through pain as we expand through pleasure, or at least I hope we do, because risk is inherent to everything we do in life. The expansiveness of risk is what facilitates the space for possibility, and they go hand in hand. How much you’re willing to risk for human connection is your choice, and that can’t be priced, it shouldn’t be ever.

My point is that the model was always wrong because it assumed the underlying was stable. I have spent my whole life being the fat tail in every distribution of virtually every system I have operated in and I am not interested in being priced by a bell curve that says I shouldn’t exist. I’m also not a fan of certain thresholds and I know how many standard deviations before I draw the line. And desire allows us to derive that point if we ask ourselves honestly what it is we need versus what we want versus where we are going and how. It’s worth the risk of attraction, in my view.

After all, desire is also representative of possibility, for any possible future, implied to then be realized. Sometimes the price of an option is worth the glimpse of the upside. Sometimes some markets are so chaotic that the only thing you can do is acknowledge the reality of this to see if it sorts itself out. Sometimes you just keep your options open and dip when someone else arbitrages or a delisting event occurs. Anything can happen.

Love means never having to say you’re sorry, according to the 1970 film Love Story. They got it all wrong. You definitely have times in your life where you have to say and mean that you’re sorry. What they should have understood is that love is long vol. Love has always been long vol. Just read the posts from early investors on Palantir’s subreddit and you’ll see it in action.

Besides, this isn’t love. It’s only a kiss, it was only a kiss, which I just know a wedding I’ll be going to in Idaho is going to play a rendition of this millennial classic and I’m dreading it already because the better nostalgia play really is “When You Were Young”. I don’t expect anything from this man. I don’t even know what he’d say to me. He is, however, to my surprise, a damn good kisser, and that particular premium was worth every penny. Maybe. I think the move here is to let the volatility do what volatility does, which is resolve on its own timeline. There’s plenty of other market forces to be occupied with.